Werte - Zoom, Number 14

Secularization and the declining impact of religion on moral choices in Europe

11.04.2022

For many Europeans, religion provides moral rules and regulations concerning moral choices in end-of-life issues. These religious guidelines are often reflected in politics to justify policies on important human issues such as abortion, euthanasia, and suicide. Such moral policies are more prominent on the political (and judicial) agenda in societies with a stronger religiously based party system.1 However, secularization of society is assumed to have resulted in a declining impact of religion on moral issues. Following Wilson2, who understood secularization as the declining social significance of religion, this would imply that religion is not any longer an important factor in today`s people`s lives. Although secularization is assumed to be a general trend in Europe, it is not very likely that it takes place all over Europe in the same way and to the same extent. The secularization process may be country or region specific, and the same goes for its implications.

Relationship between religious beliefs and participation and end-of-life morality

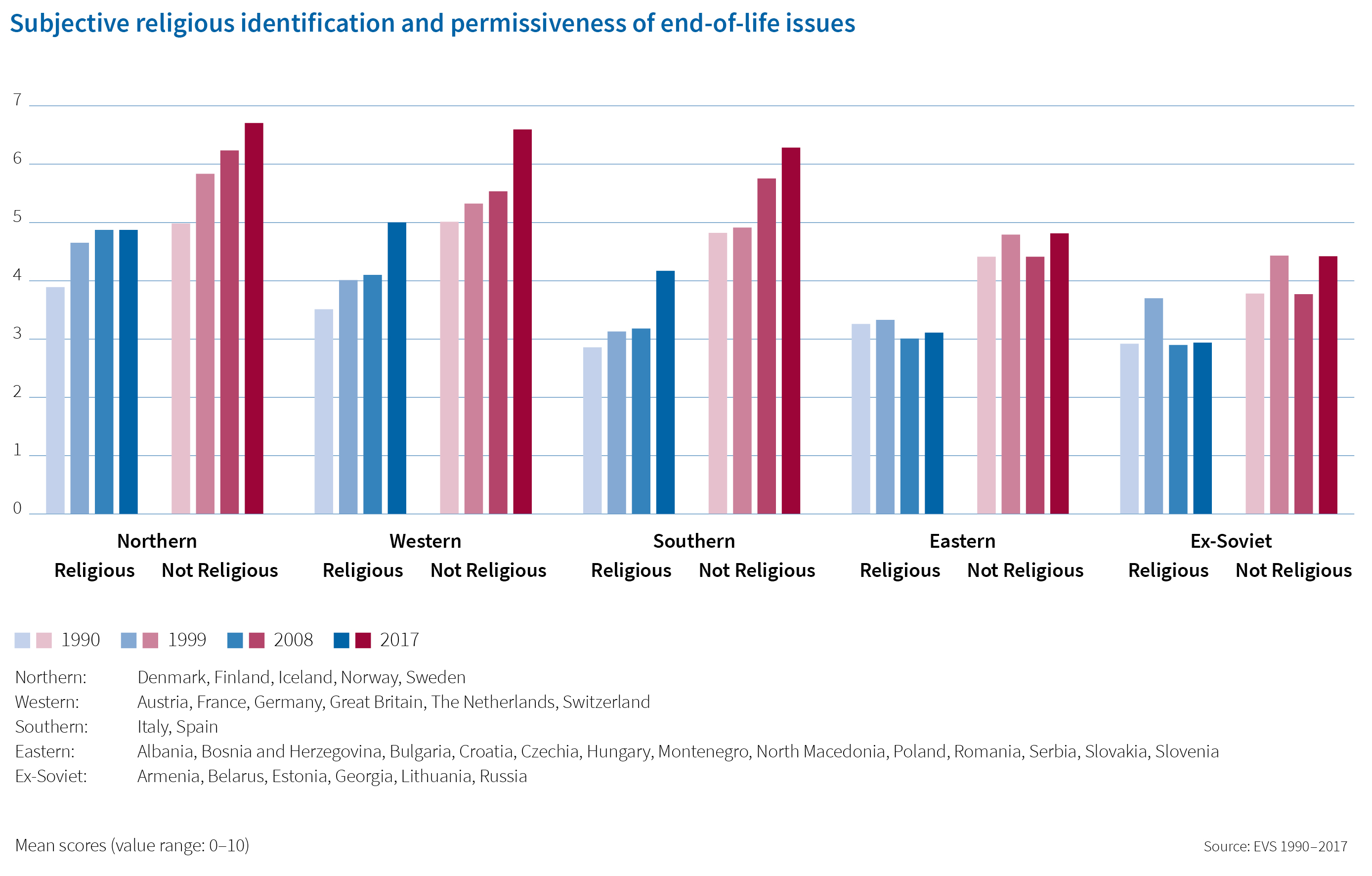

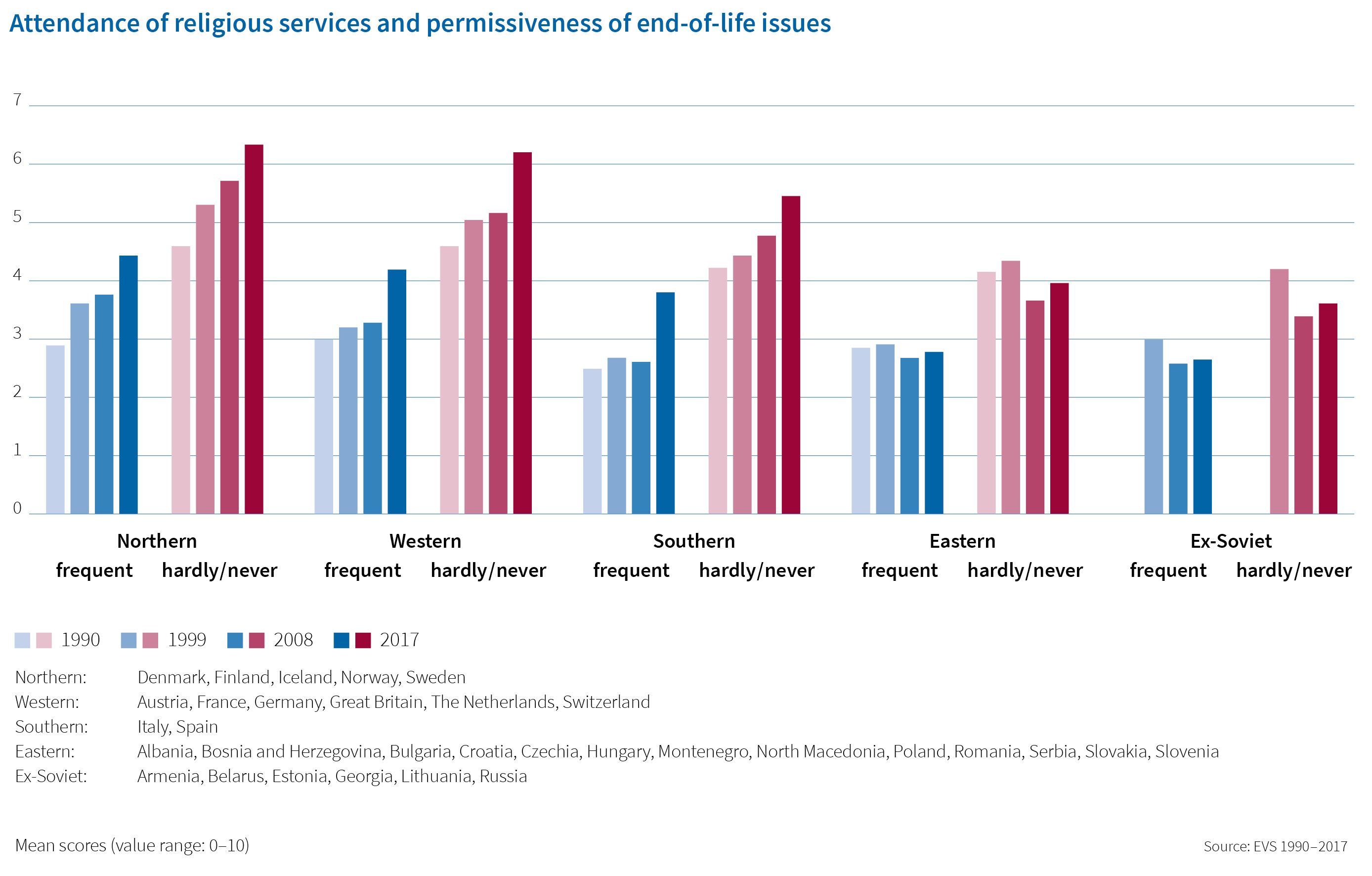

We empirically tested the secularization thesis of a declining impact of religion on moral issues such as abortion, euthanasia, and suicide in Europe. We used data from four waves of the European Values Study (1990-2017) and distinguished between five regions in Europe based on important historical and contemporary religious and secular characteristics: Northern, Western, Southern, Eastern, and ex-Soviet countries. We furthermore elaborated on the idea that religious beliefs and religious practices are distinct characteristics of religion. Subjectively identifying as religious does not imply that one is also integrated in a religion, as the latter manifests itself in attending religious services on a regular basis. We hypothesized that specifically integration in religion would remain a strong determinant for permissiveness regarding end-of-life issues, whereas religious beliefs would be decreasingly important for such moral issues.

The analyses (see the two panels in the figure) yield evidence that there does indeed appear to be a relationship between both religious beliefs and religious participation on the one hand and end-of-life morality on the other hand. As expected, religious beliefs appear less strongly associated with this kind of morality than religious attendance. Those who frequently attend religious services are clearly stricter than individuals who attend religious services less frequently or never. This substantiates the ideas of the integration perspective.

However, these results make also clear that the impact of religion on morality is not as strong as might have been anticipated, nor do the analyses provide strong evidence of declining levels of the impact of religion on morality. As such, the further secularization of society cannot be demonstrated convincingly in Europe. After all, the relationship between both indicators of religion and end-of-life morality was already modest in 1990 in all five regions in Europe and remained modest over time. In addition, many parts of Europe were already highly secularized at the end of the last century and did not secularize much further. This may hint a ceiling effect in the association between religion and morality.

Europe becomes more permissive

In addition, our analyses reveal that throughout Europe the acceptance of abortion, euthanasia, and suicide increased, not only among individuals who are non-religious and individuals who rarely or never attend religious services, but also among frequent religious attenders and believers. Although the levels of permissiveness towards end-of-life morality are lower in Eastern Europe than in Western Europe, the trend among religious and non-religious people is rather similar. Europe thus appears to become gradually more permissive, but there is not much evidence that the impact of religion has declined.

It should be noted, however, that in Eastern European countries, religious participation is not as strong a predictor of morality as subjective religiousness. The interplay between religion and morality is different in these countries compared to the rest of Europe. This may be the result of Soviet rule, when "religious organizations were strongly constrained or persecuted"3. However, this breakdown of religious institutions did not destroy personal religious beliefs. Further, as Ančić and Zrinščak4 note, the competencies of the church as a religious institution mainly concern social issues, and not so much questions of personal morality. This implies that differences between individuals who regularly attend religious services and those who rarely or never do so are less pronounced5.

The analyses do support the idea of path dependency, however. Each region, and within each region, each country appears to follow its own trajectory of secularization, with its own consequences regarding end-of-life morality. Inglehart and co-authors convincingly demonstrated that although countries develop in a similar direction they do not converge. The trajectories of change in religion and moral views they folloew are country specific and determined by historical, economic, and political legacies. Such legacies cannot be denied and determine a country`s position on the global cultural map.6 Country-specific in-depth analyses are required to address that issue.

To conclude, our study reveals that morality is still connected to religious practice and religious beliefs in contemporary secularized Europe. However, the associations are not very strong and they hardly changed over time, which means that in Europe, end-of-life morality was and is not strongly dependent upon religion. One could argue that religious institutions, being closely connected to religious practice, and religious belief systems such as subjective religiousness, are not the main drivers of end-of-life morality in today`s Europe. This begs the question as to what new drivers of morality could be.

Inge Sieben, Loek Halman

Note: This text is an abridged version of a contribution to the volume "Values - Politics - Religion", which will be published by Springer in fall 2022.

Dr. Inge Sieben is Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology at the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences of Tilburg University (The Netherlands). Her research interest are the comparative (cross-national and longitudinal) study of moral and family values. She coordinates the Erasmus+ KA2 project European Values in Education (EVALUE) project.

Contact: i.j.p.sieben@tilburguniversity.edu

Dr. Loek Halman was Associate Professor of Sociology at the Department of Sociology at the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Tilburg University (The Netherlands). He has been involved in the EVS project since 1984, first as a junior researcher, later as secretary to the EVS Foundation, member and chair of the EVS Executive Committee, and coordinator of the 1999 and 2008 EVS waves in the Netherlands.

Contact: loek.halman@tilburguniversity.edu

Annotations:

2 Wilson, B. (1982). Religion in sociological perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

5 Ančić, B., & Zrinščak, S. (2012). Religion in Central European societies: Its social role and people`s expectations. Religion and Society in Central and Eastern Europe 5(1), 21-38; Halman, L., & van Ingen, E. (2015). Secularization and changing moral views: European trends in church attendance and views on homosexuality, divorce, abortion, and euthanasia. European Sociological Review 31(5), 616-627.

6 Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; Inglehart, R. (2018). Modernization, existential security, and cultural change. In M. Gelfand, C. Y. Chiu, & Y-Y. Hong (Eds.), Handbook of advances in culture and psychology, 7. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. Cambridge: Cambdrige University Press.